2 Corinthians 11:24-28; 12:7b-10

She trapped me in the elevator at the hospital one day. She had come there to visit my mother, who was in her third year of battling cancer. She was a great believer in the healing power of prayer and had come to lay hands on my mother and pray. After she left, I waited a few minutes before leaving to run some errands, hoping to avoid any conversation with her. I knew that if I had to speak to her – or more to the point, listen to her – it would only make me angry. When I went around the corner to the elevator, she was still waiting for it to reach our floor.

As luck would have it, we were the only two people on the elevator car all the way down. The woman began to ask me questions about how I prayed for my mother. Did I really believe God could heal her? Did I pray for her healing with complete faith that God would grant it? Of course I prayed for her to be healed, but I also prayed that God would give her strength to bear it if no healing took place. This woman then told me that if I didn’t pray for my mother’s healing with complete confidence that she would be healed, then I could not expect God to make her well. This woman believed that it was God’s will for everyone to be healthy and happy, and if healing doesn’t come in answer to prayer, it isn’t because God didn’t want to or couldn’t heal the person, but because the one praying lacked faith or left some sin unconfessed. This woman also had the nerve to say that my mother had to pray only in expectation for healing, and that she was hedging her bets when she prayed for strength or courage or faith to deal with having a terminal illness. In other words, it was my fault or my mother’s fault that she didn’t get well, because we didn’t have enough faith.

I managed to keep my mouth shut all the way down to the ground floor. I knew that I was very close to saying something that I shouldn’t say to this woman. It may have been the only time in my adult life that I was angry enough to actually hit someone. How could she actually blame me or my mother or our family and friends for the fact that God may not heal my mother? I couldn’t even think of where to begin to answer her.

But if that situation were to happen today, I would know exactly what to say. I would tell her that sometimes it takes more faith to believe in God when you’re not healed than it does when you are healed. To suffer and not become angry, to trust in God even when God doesn’t make you well, takes tremendous strength and commitment and faith. I would remind her of the book of Job. Job’s friends came to him after he had lost all his possessions, his children, and even his health, and said to Job that he must have sinned so badly that this was God’s punishment for his sin. But the story played out through the next chapters of the book and continued to affirm that Job was a righteous man who had not sinned, and that it was Satan who had brought those things on Job to test his faith. I would tell her that even though much of the Old Testament teaches that people suffer when they sin, or even when their parents sin, but that Jesus said that sin did not lead to illness.

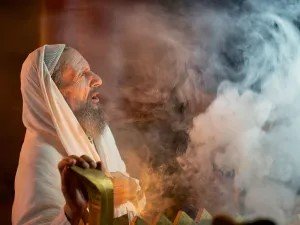

I would especially want to remind this woman about the experience of Paul as he described it here in 2 Corinthians 12. Paul had some physical problem that he called his “thorn in the flesh.” No one knows what that was; Biblical scholars have speculated that it might have been anything from migraine headaches to epilepsy to clinical depression. But even though Paul prayed three times that God would remove this thorn; God’s answer was “no.” God did not remove the thorn, in spite of Paul’s prayers and Paul’s faith. God did not take Paul’s pain away, but instead God gave Paul the strength to bear the pain. God told Paul, “My grace is sufficient for you.”

Paul needed that grace, not only for the “thorn,” but also for all sorts of other troubles he encountered in his travels. In chapter 11, Paul listed some of them. He endured acts of physical violence, such as beatings, whippings, stonings, or imprisonments. He endured hardships, such as torture and bodily pain. He endured being pursued by an enemy, such as the hostile Jews who followed him from town to town stirring up people against him. And he endured difficulties; the word in Greek literally means “caught in a tight corner with no apparent way of escape.”

And yet through all of that, Paul managed to hold onto his faith. How? How could he keep believing in a God who would let him suffer so much? It was by God’s all-sufficient grace. The grace of God did not come in the ways Paul might have expected. It did not suddenly remove every problem from Paul’s life, nor did it heal all of his broken places. Rather, the grace of God demonstrated that it was in Paul’s weakness that God’s strength was made perfect. In this great paradox, when we are most weak, then we are most strong, because it is in the weak times that God’s strength fills us more.

Lewis B. Smedes wrote in his book, How Can It Be All Right When Everything is Wrong?, describes grace like this:

Grace does not make everything right. Grace’s trick is to show us that it is right for us to live; that it is truly good, wonderful even, for us to be breathing and feeling at the same time that everything clustering around us is wholly wretched. Grace is not a ticket to Fantasy Island; Fantasy Island is dreamy fiction. Grace is not a potion to charm life to our liking; charms are magic. Grace does not cure all our cancers, transform all our kids into winners, or send us all soaring into the high skies of success. Grace is rather an amazing power to look earthy reality full in the face, see its sad and tragic edges, feel its cruel cuts, join in the primeval chorus against its outrageous unfairness, and yet feel in your deepest being that it is good and right for you to be alive on God’s good earth. Grace is power, I say, to see life very clearly, admit it is sometimes all wrong, and still know that somehow, in the center of your life, “It’s all right.” This is one reason we call it amazing grace.

I would like to close with the words to a song written and recorded by Steven Curtis Chapman, a contemporary Christian musician:

I can do all things through Christ who gives me strength

But sometimes I wonder what He can do through me

No great success to show, no glory on my own

Yet in my weakness He is there to let me know

His strength is perfect when my strength is gone

He’ll carry us when we can’t carry on

Raised in His power, the weak become strong

His strength is perfect, His strength is perfect

We can only know the power that He holds

When we truly see how deep our weakness goes

His strength in us begins where ours comes to an end

He hears our humble cry and proves again

His strength is perfect when our strength is gone

He’ll carry us when we can’t carry on

Raised in his power, the weak become strong

His strength is perfect, his strength is perfect